After reading this chapter, I was interested in finding out more about binary and multiple star systems. As it turns out, systems with more than two stars are often inherently unstable, as the system's center of gravity is constantly moving. The stars found in systems like this are usually very young, as it doesn't take long for one or more of the stars to be ejected from the system in order to form a more stable system. Here's a screenshot from a simulation of a planet's motion around two stationary stars (although it can easily be thought about as a third smaller star):

Given how complicated and random this motion already appears, it's easy to see that it would be even more unstable if the two suns were moving and exerting gravitational influence on each other as well.

|

| I don't know about you, but I wouldn't want to live in a solar system that looked like this. |

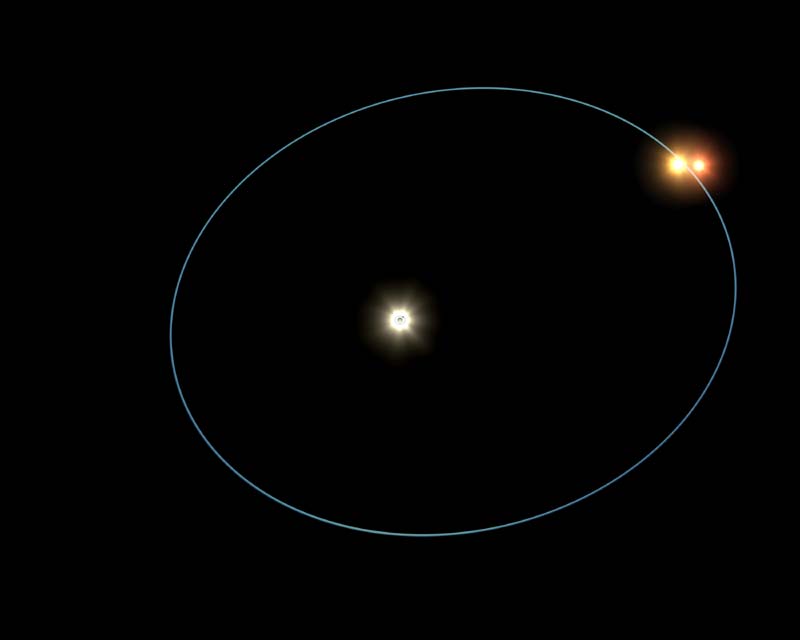

We know of star systems with multiplicities up to 7, but in most cases, these systems can be broken down into binary systems with some sort of hierarchy: for example, a binary star system orbiting a third star that's more distant. These orbits are much more stable, since the binary pair can be treated like a single gravitational source, thereby simplifying the system as a whole back down to sort of a pseudo-binary system. Presumably you could figure out the masses of the stars in a system like this using the same kind of calculation as you would for a normal binary system--but in this case, I think the orbits are much more interesting than the masses.

|

| The system HD 188753, which is a triple star system |

Sources

Astrophysics in a Nusthell, Dan Moaz

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Star_system

http://www.clausewitz.com/mobile/chaosdemos.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HD_188753

Great in-depth follow-up of the reading.

ReplyDelete